Colours (iss. 124)

|

Colours (iss. 124) |

Back to change notice |

|

Colours of military bikes

(or military vehicles in general) have been source for discussions for a long time.

At first Steve Madden's (co-author

of "British Forces Motorcycles 1925-1945 The issue of colours will maybe never be fully solved. Yes there were rules and regulations and yes "there was a war on" leading to supply problems and other deviations. Both articles of Steve and Mike give a good insight and I regard them as complementary to each other. At the bottom I have added the

abbreviations and explanations thereof, as found in the text, as well as some

deviating colour schemes, paint application practices and postwar

colouring of ex-military bikes.

|

|

By Steve Madden,

Military colours

"In

response to the recent interest in the colours of military

motorcycles, I have a little bit more information on the subject of

WWII British motorcycle paint finishes. It has been generally held

that British WWII military motorcycles were painted in every shade

of khaki imaginable, any finish being correct. There is a certain

element of truth in this statement, although the official War

department policy was a little more definitive. As with everything

in the military world, there were official directives affecting the

colour of paint used on vehicles. This standard was maintained

throughout the war by the issuance of WD directives specifying paint

colours and describing the actual shades in some detail,

at one point comparing shades of brown used to a selection of

cups of tea and coffee! Later

on, the various shades employed were allocated British Standard (BS)

codes to enable colours to be mixed with some degree of accuracy. Generally,

motorcycles and spare parts from each manufacturer would be

factory-painted (usually by spray-painting) during production. With

few exceptions, all machines were painted at component stage and,

when new, retained all fasteners and ancillary components in the

appropriate finishes of the period (dull-cadmium, dull-chrome and

cosletised finishes). The

motorcycle manufacturers, in return, obtained supplies of paint from

external contractors who were producing en-masse for every other

manufacturer involved in war time production. Paint supplies were

generally prepared from colour samples supplied, themselves subject

to some shade variation, rather then the later BS coding enabling

mixing to be completed with some accuracy. However,

although paint suppliers were working to the WD specifications, the

large numbers involved resulted in wide variance of shade.

Hence-dark earth-brown could theoretically have numerous variations,

all of them technically correct. Today, it is rare to find a war

time WD motorcycle still bearing the original factory finish. A more

accurate guide to original paint colour may be found by examining

new old-stock WD spares protected from fading by (usually) excellent

packing. Even here, minor variations will be found. As

a general guide, pre-WWII supplied WD motorcycles were finished in

glossy dark green. By 1939 virtually everything being supplied was

now finished in matt khaki-green, described in official sources as

“a cup of tea with milk!” By early 1944 green was again

re-introduced as the standard colour, though this time described as

“Olive drab”, which endured for the remainder of the war. Dates

of colour introduction however, were affected by WD directives

stating that the new colours were to be adapted after stocks of

existing colours were exhausted. Obviously, motorcycle manufacturers

would use less paint then a manufacturer of trucks,

so in certain cases the older shades on new motorcycles

continued to be applied for some time. WD

motorcycles were often repainted at local level, whether following a

workshop rebuild or simply to smarten the machine. Paint would be

drawn from unit stores and could be literally any variation of the

standard shades. In

some instances, paint was mixed locally, further adding to the shade

confusion. In such cases the entire machine was painted either by

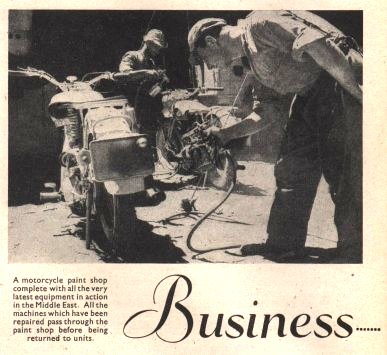

hand or spraygun -engine, gearbox, saddle, etc. To advice on one final point; few, if any, motorcycle manufacturers factory-finished machines in “desert” colours. Machines left the factories wearing standard WD colours and were delivered to various Ordnance Depots holding literally hundreds of vehicles. These depots then allocated the bikes to wherever they were required. They were not repainted by these depots. Some units in the Middle East repainted machines in desert shades once arrived, and this was usually very crudely done by brush and locally-mixed paint. However, due to the motorcycle having a small surface area, together with the fading effects of the sun and dust on paintwork, repainting was the exception rather then the rule. Another common misconception concerns RAF and Naval motorcycles. Those supplied during war time were finished by manufacturers in the same standard camouflage colours as those supplied to the Army. ‘RAF blue’ and ‘Navy blue’ finishes were generally pre and post-war only!"

|

|

By Mike Starmer, Author of a.o. "British army colours & disruptive camouflage in the United Kingdom, France and NW Europe 1936 - 1945" MOTORCYCLE COLOURS DURING WW 2: AN UPDATE. I have been asked by Rob van den Brink to write an update to the article about the military colours of motorcycles by Steve Madden some years ago. This is my attempt based on over 30 year’s research using primary regulations documents set out in chronological sequence. This is backed up the availability to me of some of the relevant colour charts. On the question of colour, I must express my most sincere thanks to one of your avid motorcycle enthusiast members, Richard Payne, who first contacted me in 2007 and later that year visited my home with components of his Norton WD16 bike, some of which he courageously left in my care whilst I attempted to formulate a model paint mix that matched the colour on these parts. This colour is believed to be Khaki Green No.3 which although written of for many years, had defied everyone concerned with military colours to accurately define or even identify colour-wise. His items were not the sole examples in the puzzle since I already had in my possession a dated steel helmet of similar but then unidentified hue, and a replicated paint sample from Canada. However Richard’s components clinched the deal as it were. It has generally been believed that military vehicles had been painted in a variety of colours according to the whim and fancy of a senior officer or NCO in charge of a unit, almost implying that vehicles had arrived from works or ordnance depots devoid of any sort of colour whatever. This of course could not be so since the surface finish and components would deteriorate during the sometimes several months period in storage. A protective coat of paint was of course applied at the works, the colour of this being specified by the War Office in the written contracts. This colour changed according to the camouflage requirements as time went on, dictated by operational requirements and chemical supply problems. These requirements were laid down in Army Council Instructions (A.C.I.) and Military Training Pamphlets (M.T.P.) at various times during the war. By and large these were adhered to although there were variations from the rules due to unusual circumstances such as sudden unit moves to overseas areas and simply lack of the correct colour being immediately available. The War Office issued contracts for specific colours and for specific purposes. For example enamel paint, spraying and enamel paint, brushing; both for wood and metal and Bituminous Emulsion for canvas. All of these types being of the same colour and, as recorded in documents, P.F.U. that is, prepared for use. The reason was that only the chemical industry could manufacture a particular colour in large amounts with any degree of colour precision and to the required performance specification. Mixing was of basic ingredients was not carried out at Depots or at unit level. The paint was issued from R.A.O.C. depots to indenting units. This means simply that a unit could not obtain unofficial colours except by local purchase via the C.O. and condoned by higher authority. A paint specification C/1577, dated 12 February 1934 was issued from the War Department for the guidance of painters mixing the colour which under diffused daylight must closely match that of ‘Deep Bronze Green No.24’ in BS 381C: This colour became the established pre-war Service Colour of Deep Bronze Green No.24. This gloss colour appears tonally very dark and glossy, the white WD numbers and battalion signs then in vogue contrast highly against this background. The war clouds looming in 1938 caused a rethink on suitable colours for possible operations, these being based on earlier 1930s colour evaluation and trials. By the end of 1938 a new colour had been selected; Nobels Khaki Green No. 3 being specified as a finished coat. The colour is a strongly saturated brownish yellow-green in the olive drab range of shades. Khaki Green No.3 appears to vary considerably in tone on photographs depending on film type and development methods. A.C.I. 96, 2 FEBRUARY 1939. ‘All vehicles (except limousine staff cars) and all tanks, guns and supporting weapons which are at present painted with service paint shall in future be painted with a standard basic camouflage paint, Khaki Green No.3.’ Not all equipment was immediately repainted of course, it was initially applied to new manufactured equipment and those currently undergoing major overhaul or repaint in workshops, therefore some of the vehicles that went to France were in their earlier overall colour of Deep Bronze Green 24. Military Training Pamphlet 20 of June 1939 described two schemes each using two of three available colours with diagrams showing how to and how not to apply the disruptive colours to vehicles. Scheme 1 used a basic colour of Khaki Green No. 3 (G3) with a disrupter of Dark Green G4 whilst for lighter conditions Light Green G5 became the basic colour whilst Khaki Green No. 3 was the disrupter. Whilst it is believed that scheme 1 was the usual scheme applied as it appears in photographs as low contrast tones, it also appears that scheme 2 may well have been used too as the sample on Richards motorcycle demonstrates. But this may only be a minority scheme. Later in 1939 “ARMY TRAINING MEMORANDUM No. 22” was issued. Under ‘ANTI-GAS DEFENCE’, the instruction was to apply a 36 square inches area patch of paste on all vehicles ahead of the driver where it may easily be seen. In the case of motorcycles this patch was applied to the top of the headlamp housing. This was still present on Richard’s headlamp housing together with small patches of the blue paint that had been applied over the lamp glass, a common feature during the wartime blackout and but one of a number of methods by which the light from headlamps was dimmed to comply with blackout restrictions.

A.C.I. 465, 15 MAY

1940; DISRUPTIVE PAINTING AND NUMBERING OF VEHICLES.

This referred to

earlier A.C.I.s 175 of 1938 and 96 of 1939 and required that all

guns and War Department vehicles (‘A’, ‘B’ and RASC) tanks, guns,

supporting weapons and War Department vehicles will be painted in

disruptive camouflage in accordance with the principles laid down in

Military Training Pamphlet No. 20 of June 1939. The War Department

number will be clearly painted in white on both sides of the bonnet

and on the rear of the vehicle. The dimensions of the letters and

figures will be:- In the case of motorcycles the number was painted on both sides of the fuel tank 1½ inches high prefixed by the letter C. Pre-war motorcycles had this number very neatly painted in smaller digits on a black panel outlined in white. This can be seen in a number of photographs taken during the early period. R.A.F. A.M.O’s had specified that from 1937 their ground vehicles will be painted BSC. No.33 R.A.F. Blue-grey and this applied to their motorcycles too. This order officially lasted until A.618 of 7 August 1941 when R.A.F. vehicle colours came under the jurisdiction of War Office colours. At the same period Royal Navy vehicles were gloss BS. No.7 Dark Blue, these too changed to the War Office directive colours. A.C.I. 1559. 23rd August 1941. By early 1941 a chronic shortage of chromium oxide chemical had become apparent which obliged the re-evaluation the camouflage colours in use. The authorities discontinued production of the two disruptive greens G4 and G5 in an effort to conserve chromium oxide and introduced a new range of suitable colours for all camouflage purposes. This range later became BS.987 ‘Camouflage Colours’ 1942, of which more later. Meantime some of the colours from this new range went into immediate production and use. Two of these S.C.C.7 (green) and S.C.C.1A (dark brown) were specified in this A.C.I. but only for canvas tilts. For wood and metal another disruptive colour, Dark Tarmac No. 4 was now introduced whilst the basic colour remained as before. Research in Canada as of 2007 indicates that this colour may be a very dark blue-grey that could be described as black when seen in conjunction with Khaki Green No. 3. A.C.I. 1559. 23rd August 1941. The bodies of vehicles were to continue to be painted with paint, spraying, Khaki Green, No. 3 and paint, spraying, Dark Tarmac No. 4 whilst the canvas covers for vehicles were to be painted with two of the new camouflage colour range which had been designed for all vehicles and building structures. A.C.I. 2202. 8 November 1941. This order was concerned mainly with the painting of canvas covers and hoods of vehicles but was in addition a warning of a fundamental change in the camouflage style shortly to be adopted. The basic colour was still Khaki Green No. 3. Military Training Pamphlet No. 46 ‘CAMOUFLAGE’; issued ultimately in 7 parts but only 3 and 4A is relevant here. Part 3 lists the new colours with idiosyncratic descriptions, not names. ‘A cup of tea with milk’ was just one such. This scheme specified that all upturned surfaces were now to be painted the darker colour and blended into the side surfaces in undulating lines both from the roof and up the sides from shadow lower areas. This particular pattern is not relevant to motorcycles but it did encompass the well known but unofficial ‘Mickey Mouse Ears’ design as applied to multi-wheeled vehicles. This is the type of patterning illustrated in M.T.P. 46/4A. Again two basic colours are specified for England and Northern Europe, Khaki Green No.3 or Standard Camouflage Colour No.2 (brown) and the dark paint disrupter should be Standard Camouflage Colour No.1A (very dark brown). The names here are occasionally used in documents simply to give the reader some idea of what the hue was, they are not official names for the colour as none were ever applied to BS 987C: The S.C.C. 2 shade has often been called ‘earth’ or ‘dark earth’ in some publications but these are merely subjective descriptions. A.C.I. 1160 of 30 MAY 1942 gave more precise details of the new scheme but now specifically called for S.C.C. 2 (brown) to be the basic colour with S.C.C. 1A or S.C.C. 14 (black) as the disruptive colour. Although the new range of camouflage colours had been in use for several months it was only in September 1942 that a formal document, BS.987C: ‘CAMOUFLAGE COLOURS’ with a range of eleven colours was first made generally available to paint and vehicle manufacturers and other interested bodies. Despite wartime constraints this B.S. included a performance specification for the paints. All of these paints being P.F.U. A.C.I. 1496 of 13 OCTOBER 1943. This A.C.I. was issued reaffirming that 'A' and 'B' vehicles were to continue to use Brown S.C.C.No.2 as the basic colour. This basic colour then continued to be applied at works and army depots until the next major change in preparation for the invasion of Europe. A.C.I. 533, 12 APRIL 1944. ‘CAMOUFLAGE. WAR EQUIPMENT, etc. CHANGE IN BASIC COLOUR. A new colour, S.C.C.15 Olive Drab was to be adopted as the new basic camouflage colour for all army equipments, in lieu of Standard Camouflage Colour No. 2 (brown), and certain new equipments painted Olive Drab were to be shortly received by units. This new colour had been specially formulated for use in forthcoming operations in Europe. It was intended to be similar in shade and tone to U.S.Army Olive Drab No.9 to avoid the need to repaint lend-lease equipments until such times as this was necessary. This means that any American built motorcycles in British and Commonwealth use initially remained the U.S. colour. The order also stipulated that vehicles will not be repainted simply to comply with the new colour regulation and will continue to be used in the early colours until repainting is due or necessary. This being the case then lots of motorcycles, ‘B’ class and other non-tactical vehicles went to France in their earlier brown colours with dark brown or black disrupter as required. I must mention one other point about motorcycles in the Middle East. It was usual for vehicles to be sent abroad in the UK basic colour since at the time of dispatch there was uncertainty that the ultimate destination would not change during transit, as in fact often occurred. After arrival in Egypt the vehicle would be taken to a major depot for overhaul and preparation for desert use which included a repaint in the colour/s as specified in local orders. In 1940 and 1941 a tri-coloured scheme was in use on all vehicles and AFVs which is generally referred to as ‘Caunter Scheme’ although this is not an official title. In the case of motorcycles a simple drawing was issued for this scheme which used only two of the specified colours, Light or Portland Stone 61 & 64 respectively as a basic colour with Slate No.34 as a disrupter. The pattern was actually applied as I have photographs of it applied to both solo and combination machines. From early 1942 only one of the two basic colours were applied and then in October of 1942 the colour changed to Desert Pink Z.I. (Zinc Iron), an earthy pink like a common house brick. Again repainting was not carried out until due or necessary.

Hopefully this article has not been too long and boring, I have of necessity omitted many aspects of the orders but all of the basics are here. Now you can go ahead with confidence to restore your military machines accurately. Michael Starmer 2008.

|

|

Although given through the text the Abbreviations used in this article are summerised below:

A.C.I. :

Army Council Instructions

|

|

Here a description of the colours given by Mike and mixes to make examples:

SCC 1A very dark brown is like RAL 8014 but darker.

SCC 2 brown like FS 20095.

Light Stone 61 very close to RAL1002 and FS 20260.

Portland Stone 64 very close to RAL 1014 but more like FS 33564

towards 33685.

Slate 34 similar to FS 34102 but should be more grey.

Desert Pink Z.I. (Zinc Iron), similar to a British common house brick, an

earthy shade about FS33531 to 30450. Humbrol 121 is a lighter

version and would be OK on a 1/76 scale model. The nearer mix is

4 parts H34 + 1 part H118 and this may be a bit light then. The

pink shade applied to many restored jeep types is far too vivid.

It was a colour used for a limited period post-war.

Mixes: So that readers who wish to may buy the model paints and try these for themselves to get an idea of the true colours. H is Humbrol paint, R is Revell paints, all enamels. (Mixes by volume).

DEEP BRONZE GREEN 24; 6 X H2 + 4 X R84 + 1 X H33.

KHAKI GREEN G3; 12 X R361 + 5 X R360 + 7 X R84.

This is critical on proportions.

DARK GREEN G4; Provisional mix. 8 X R361 + 1 X R8.

LIGHT GREEN G5; Provisional. R 361 only.

LIGHT STONE 61; 6 X H74 + 1 X H26.

PORTLAND STONE 64; 7 X H196 + 2 X H34 + 2H74.

SCC 2 (brown); 5 x R86 + 6 X R84.

DESERT PINK ZI; 4 X H34 + 1 X H118.

SCC 15 OLIVE DRAB; 5 X H150 + 5 X H159 + 2 X H33.

|

|

Special colour schemes: A special colour scheme was used on the island of Malta. See Malta colourscheme page for more details.

|

Personal remark:

Bikes were painted at component level

by the manufacturer. The

original WD16H

specifiation does give a good indication to the level of detail

of different parts finishes. |

|

Post war, many motorcycles were civilianised by painting them black with silver grey painted petrol tank and removing the obvious military additions like Vokes filters, black-out masks, trails front forks bump stops, crankcase bash shield, tubular foot rests, pannier carriers and bags, canvas handlebar grips etc. A more limited amount can be found in all kinds of colours and different levels of chrome on them. In the early post war times, chrome was expensive and scarce, the riders short of money. Much chromed bikes are therefore a folly of recent times. Bikes returning from India often "suffer" from this extravaganza. Most 16H motorcycles found today are in the black and silver guise with various degrees of petrol tank lining resembling the original Norton practices. Just remember, whatever colour they have, they are fun to ride!

|